ligament injuries occur 2–8 times more often among female athletes than their male colleagues. these injuries are not just more prevalent, but also more likely to be career ending.

even though it is known that menstrual hormones influence ligament laxity, the body of research into these effects and how to mitigate associated injury risk, is disappointingly small. as women’s sport gains a global stage, it is time to demystify these hormones and the female body. expecting everyone to function in line with the 24hr testosterone cycle perpetuates inequity not just in sport, but in people’s work, education and health outcomes.

two quick notes:

- equity and equality are not the same. equality means everyone is treated the same; equity recognises that individuals have different circumstances and need different resources to reach an equal outcome.

- women are not the only people that menstruate. i will go on to mention female athletes and women’s sport, but this is relevant to anyone with a uterus. unfortunately the world of professional sport is significantly behind in terms of queer recognition.

so, what do we know?

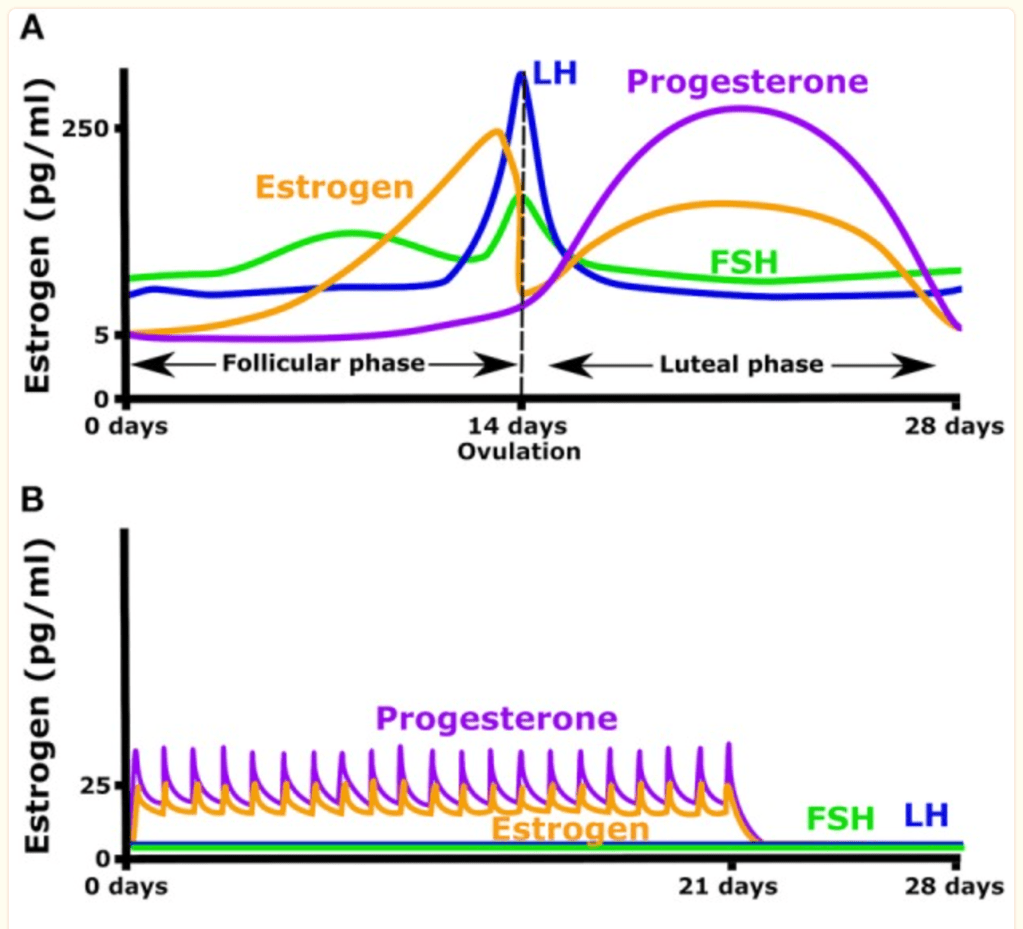

the hormones involved in the menstrual cycle change in a sophisticated dance to allow ovulation and menstruation. we will assume a generalised cycle where ovulation is happening for simplicity here, but there is so much variation between bodies. day 0 is the first day that you bleed, and the start of the hormonal cycle.

during menstruation, FSH, LH, oestrogen and progesterone are all at low levels. oestrogen levels increase gradually throughout menstruation and peak around day 12. studies have reported that knee ligament laxity increases in direct correlation with increased oestrogen.

research shows that there is an increased likelihood of ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injuries grouped around day 12 of the menstrual cycle, in line with peak oestrogen levels.

there is popular opinion within the sporting community that athletes who menstruate should take oral contraceptives to reduce their risk of injury related to hormonal changes.

there are two kinds of oral contraceptives; combined oestrogen-progesterone pill or progesterone only pills.

combined pills provide a daily low level of oestrogen and progesterone. these pills maintain steady estradiol levels throughout the cycle and decrease the ovulatory rise in oestrogen. this daily dose of oestrogen and or progesterone also eliminates the cyclic rise in LH and FSH.

it is known that very high doses of progesterone inhibit muscle protein synthesis, but low levels do not impact. as such, progesterone only pills may be less suitable for athletes. the concentration of progesterone in the combined pill has not been found to have any negative impact on muscle proteins.

while peaks in oestrogen levels increase ligament laxity, this hormone also has positive impacts on tendon, muscle and bone. oestrogen also decreases tendon stiffness, which reduces the risk of muscular injuries – female athletes experience 54% fewer muscle tears than male. oestrogen also increases collagen production in tendons, and promotes the uptake of new collagen fibres into tendons following exercise. the hormone also has an anabolic effect, meaning muscles will increase in size and strength in response to exercise. finally, bone growth and density is increased in response to oestrogen.

this research indicates that normal hormonal cycling increases musculoskeletal adaptation to training, and a recent systematic review suggests that athletes should maintain this cycle for best results during off season, or the base phase of their training. if they are considering taking an oral contraceptive to reduce ligament laxity, they should start this as they shift into their competitive season. a combined contraceptive rather than progesterone only is recommended.

in this scenario, training would be performed in the absence of OCs and therefore lower tendon stiffness, and induce higher anabolic responses to training and maximal muscle repair on hard days. this would result in fewer muscle pulls and a greater metabolic cost of training, increasing the likelihood of a healthy build up phase. taking a low progesterone OC in season would help increase stiffness within tendon and ligament while not preventing muscle repair. this allows athletes to maximise performance (from greater force development) while reducing risk of musculoskeletal injuries during the competitive season.

of course, hormones are not the only thing which influence an athletes risk of injury. current research calls for an investigation of the physiological, biomechanical, functional, but also psychological and behavioural variables that influence injury risk in female athletes.

possibly the most significant factor that causes injury disparity is resource and training inequalities.

it is also crucial to consider the context of women’s sport – until very recently it did not have the stage or audience to generate revenue like the mens leagues. most elite male athletes have had access to high quality coaching and specific injury prevention training programs, that their female peers have not. in the recent fifa womens world cup, many of the athletes did not earn enough to be full time athletes – they work other jobs to support themselves. the underlying assumption that men and women are situated in equivalent training contexts is inaccurate.

the good news is that women’s sport is undeniably profitable. the need for female specific injury research and better resources for womens sport is clear and finally there is money behind it.

if you are any kind of mover, understanding how your body works is crucial to building a respectful relationship with it, and a sustainable movement practice. speaking openly about all bodies is an act of radical resistance against systems of gender inequity.

references

https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/55/17/984

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2325967117718781